John Hanning Speke, 1827-1864.

DNB Entry

Times Obituary and Inquest Report.

H.B. Thomas on Speke's Death

Speke accompanied Richard Francis Burton on his 1854-5 Somali Expedition, then again on the 1857-9 East Africa expedition, which aimed to find the sources of the Nile. The expedition discovered Lake Tanganyika in 1858, and explored part of its extent. Speke supposed that Lake Victoria, which he discovered and named, while off on a foray of his own to the North of the chief route of the expedition, was the source of the Nile.

Speke later returned to lead his own expedition, 1860-3, accompanied by James Augustus Grant. They confirmed that Lake Victoria is the chief reservoir of the Nile, though controversy over the question was kept alive for another decade, largely because of Burton's vigorous opposition. Burton supposed the Tanganyika was the Nile reservoir, and that Victoria was a seasonal collection of lakes or lagoons with no outlet. Speke died in a hunting accident in 1864.

Articles

'Journal of a Cruise on the Tanganyika Lake' and 'Captain J. H. Speke's Discovery of the Victoria N'Yanza Lake, Supposedly the Source of the Nile',

Blackwood's Magazine, 1859.'Captain Speke's Adventures in Somali Land',

Blackwood's Magazine, 1860.

Books

My Second Expedition to Eastern Intertropical Africa

An exceptionally rare pamphlet.

Saul Solomon, Cape Town, 1860.

PDF Page Images.Journal of the Discovery of the Nile Sources.

First edition of 1863.

Blackwood, London.PDF Page Images.

HTML Transcription.What Led to the Discovery of the Nile.

First edition of 1864.

Blackwood, London.PDF Page Images.

HTML Transcription.

Dictionary of National Biography Entry [1897, WILLIAM CARR] :

(with minor corrections of fact)

SPEKE, JOHN HANNING (1827–1864), African explorer and discoverer of the source of the Nile, second son of William Speke (1798–1887) of Jordans, near Ilminster, Somerset, by Georgina Elizabeth, daughter of William Hanning of Dillington, was born at Jordans on 4 May 1827. His father, who had been a captain in the 14th dragoons, was the representative of a younger branch of the ancient family of Speke of White Lackington [see Speke, Hugh] (Collinson, Hist. Somerset, i. 69). From his childhood Speke was educated for the army, and entered the 46th regiment Bengal native infantry (1844). He served through the Punjab campaign under Sir Hugh, first viscount Gough [q. v.], and was present during the Sikh war at the battles of Rámnagar, Sadullápur, Chilianwala, and Gujarat, acting in Sir Colin Campbell's division. He was promoted lieutenant 1850 and captain 1852. At the close of the war Speke appears first to have conceived the idea of exploring Central Equatorial Africa (What led to the Discovery of the Nile, p. 1), and all the leave of absence which he could secure in India he spent in hunting and exploring expeditions over the Himalayas and in unknown portions of Thibet, during which he proved himself a competent sportsman, botanist, and geologist. Having completed his ten years' service in India, 3 Sept. 1854, he left Calcutta the following day for Aden, intending to put in effect the scheme he had formed for African exploration. He arrived at Aden at a moment when an expedition was being organised by the Bombay government, under the command of Lieutenant (afterwards Sir Richard) Burton, for the purpose of investigating the Somali country. At the suggestion of Colonel (afterwards Sir James) Outram [q. v.], Speke was put on service duty as a member of the expedition. He was at first despatched, 18 Oct. 1854, in preparation for the main journey, to Bunder Gori, with instructions to penetrate the country southwards as far as possible, to inspect the Wadi Nogul, and eventually to join the rest of the expedition at Berbera. But mainly owing to the unsatisfactory character of his headman or guide, who took advantage of his ignorance of the language, he was compelled to return to Aden, 15 Feb. 1855, without accomplishing the object of the journey. On 21 March 1855 he started again for Berbera, arriving there 3 April. Many camels had been got together, and great preparations had been made for the advance, but the expedition was doomed to failure, a night attack being made on the camp by the Somalis, in which Speke was dangerously wounded. Leaving Aden on sick certificate, Speke arrived in England in June 1855, and almost immediately volunteered for the Crimean campaign. He was attached to a regiment of Turks, with the commission of captain, and proceeded to Kertch in the Crimea, where he served until the close of the war. On its termination he meditated exploration in the Caucasus, but abandoned the idea on receiving an invitation from Burton to join in another African expedition. The new expedition was undertaken at the joint expense of the home and Indian governments, and at the recommendation of Lord Elphinstone, then governor of Bombay, Speke was officially appointed a member of the party. The instructions of the Royal Geographical Society to Burton were to penetrate inland from Kilwa or some other place on the east coast of Africa, and make the best way to the reputed lake of Nyassa, to determine the position and limits of that lake, and to explore the country around it.

On 3 Dec. 1856 the expedition, under the command of Burton, sailed in the East India Company's sloop Elphinstone from Bombay to Zanzibar, where they arrived on 21 Dec. The journey inland was not commenced until 27 June 1857, the six months preceding being occupied in exploring the coast and determining the best line of march. Starting from Kaolé and proceeding in a south-west direction as far as Zungomero, and then north-west through Ugogo and Ukimba, the travellers arrived at Kazé, south latitude 5°, east longitude 33°, on 7 Nov. 1857. Here they received information of three inland lakes from an Arab trader, Sheik Snay, which first led Speke to entertain the idea that the most northern lake might prove to be the source of the Nile. Moving slowly forward, owing to the illness of Burton, they reached Kawelé, on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, January 1858; here great difficulties were experienced with the native chief, Kannina, whose protection was only to be bought by heavy tribute, and who threw all possible obstacles in the way of their navigation of the lake. Both the explorers were for some time completely disabled, Burton from fever, Speke from ophthalmia; but on 3 March 1858 the latter embarked in a canoe, and crossed the centre of Lake Tanganyika, east to west, from Kabogo to Kasenge. At the latter place he noted, and subsequently put down in his maps, what he believed to be the western horn of the Mountains of the Moon encircling the north of the lake. At Kasenge Speke was given by the Sheik Hamed a full description of the Lake Tanganyika, but his efforts to secure the loan or purchase of a dhow proved unavailing, and he recrossed and joined Burton, 31 March. Both travellers now in company made a partial examination of the lake from canoes, but before it was completely navigated they were compelled, owing to Burton's ill-health and the fact that their supplies were running short, to return to Kazé, where they arrived towards the end of June, having adopted a slightly more northerly route than that by which they came. Here Speke persuaded Burton to permit him to make an attempt to visit the larger northern lake (Victoria Nyanza), while Burton remained at Kazé, making the necessary arrangements for their return journey.

On 9 July 1858 Speke, with thirty-five followers, provided with supplies for six weeks, left Kazé, and, marching due north for twenty-five days, arrived 30 July at a creek forming the most southern point of the great lake, and on 3 Aug. he secured his first complete view of it, and named it Victoria Nyanza. After taking compass bearings of the principal features of the lake, and securing such information as he was able to get on the spot, he started on his return 6 Aug. and rejoined Burton at Kazé 25 Aug. He immediately expressed his belief that he had discovered the source of the Nile, but on this point his fellow traveller was sceptical, and a coolness between the two explorers, arising in the first instance from this difference of opinion, subsequently increased and destroyed their old friendship. The expedition now returned to Zanzibar, and Speke, leaving Burton, still sick and unfit to travel, at Zanzibar, availed himself of a passage home offered in H.M.S. Furious, and arrived in England 8 May 1859. He there communicated with the Royal Geographical Society, lectured at Burlington House on the discovery of the two lakes (Tanganyika and Victoria Nyanza), and practically arranged with Sir Roderick Impey Murchison [q. v.], president of the Royal Geographical Society, the plans of a new expedition which he was to lead. Burton's arrival on 21 May and Speke's somewhat unnecessary haste in announcing the results of the expedition accentuated the already strained relations between the two travellers. The rupture became complete when Speke, in two articles in ‘Blackwood's Magazine,’ openly assumed the main credit of the expedition and expressed the view that the Victoria Nyanza was the source of the Nile. These articles were answered by Burton in his book, ‘The Lake Regions of Equatorial Africa,’ in which he criticised Speke's Nile theory and ridiculed his imaginary discovery of the Mountains of the Moon. Both travellers received from the French Geographical Society the medal awarded for the most important discovery of the year. Speke was almost immediately engaged in preparations for the new expedition, of which, through the support of Sir Roderick Murchison, he was given the command. He started from England 27 April 1860, with Captain James Augustus Grant [q. v.] (1827–1892), an old friend and officer in the Indian army. The objects of the expedition, which was organised by the Royal Geographical Society and supported by the government by a grant of 2,500l., were to explore the Victoria Nyanza and to verify, if possible, Speke's view as to that lake being the source of the Nile. The expedition also received from the home government assistance in the passage by sea; the Indian government granted arms, ammunition, and presents for chiefs in the interior, and the Cape parliament gave 300l. and the services of ten men from the Cape mounted rifle corps. The route taken was in the first instance the same as on the previous occasion, and the party, consisting of 217 persons, bearers and armed men included, left Zanzibar on 25 Sept. 1860, and arrived at Kazé on 24 Jan. 1861. To this base of operations Speke had sent on beforehand a considerable quantity of cloth and beads. Very great difficulty was now experienced in making a further forward movement, owing to the scarcity of carriers, warfare between the Arabs and natives, and the extreme rapacity of the small chiefs through whose country it was necessary to pass. From July to September Speke was seriously ill, and in September Grant, while leading a separate portion of the caravan in the territory of the chief Myonga, was attacked and plundered. Rejoining each other on 26 Sept., they marched north between the lakes Tanganyika and the Victoria Nyanza, through Bogue and Wanga, and arrived in November 1861 in Karague, where they were treated with great hospitality by the king, Rumanika. Leaving Grant invalidated in the care of Rumanika on 10 Jan. 1862, Speke proceeded north into Uganda. On 19 Feb. he arrived at the palace of Mtesa, the king of Uganda; here he was rejoined by Grant in May, and after tedious negotiations, extending over four months, he persuaded Mtesa, who on the whole treated him in a very friendly fashion, to facilitate the progress of the expedition northwards through the territory of Kamrasi, the king of Unyoro. The party left the capital of Uganda on 7 July, and, marching round the north-west shoulder of the Victoria Nyanza, struck the Nile at Urondogani on 21 July. Before the Nile was reached Grant was despatched with the bulk of the property to Chagusi, the capital of Unyoro. After trying in vain to secure boats in which to ascend the stream, Speke marched up the left bank, and on 28 July he reached the place where the Nile leaves the Victoria Nyanza, and named it Ripon Falls, after Lord Ripon, under-secretary of state for war, under whose auspices his expedition had been arranged by the Royal Geographical Society. Not being allowed by Mtesa's officers to do more than examine the falls, Speke started on his return down the stream on 31 July. With great difficulty he secured boats and attempted to continue his journey on the Nile, leaving Urondogani on 13 Aug., but was obliged to abandon the river owing to the hostility of the natives, and was only allowed, after long negotiation, to enter Unyoro by land. Not till 9 Sept. was he permitted to approach the palace of Kamrasi, the extremely suspicious king of Unyoro (N. lat. 1° 37′ 43″ E. long. 32° 19′ 49″). It was as difficult to get away from Kamrasi as it had been in the first instance to approach him, and Speke was not allowed to pass on his road north until 9 Nov., and then only at the cost of his last and best chronometer. Following the river, he reached the Karuma Falls on 19 Nov., here, where the Nile begins to make its great bend to the west, he was obliged to leave the stream owing to native warfare, and, travelling down the chord of the arc made by the river, he reached De Bono's ivory outpost (N. lat. 3° 10′ 37″) on 3 Dec. On 13 Jan. 1863 Speke, now marching with a contingent of Turks from the ivory station, reached Paira, within sight of the Nile, and thence travelling down the right bank of the stream by Apuddo, Madi, Marsan, and Doro, he arrived at Gondoroko on 15 Feb. Here he was met, and given cordial assistance, by Samuel (afterwards Sir Samuel) Baker, who, at his own expense, had organised another expedition. To Baker Speke gave willingly all the information he possessed as to the lake Luta Nzigé (Albert Nyanza), in and out of which he was well aware that the Nile flowed, but he erroneously regarded that lake as a backwater of the Nile. He planned the route by which Baker should go, and gave him a map of remarkable accuracy, considering that part of it was drawn on hearsay evidence; the map is now in the possession of the Royal Geographical Society. He thus enabled Baker to make his successful discovery of the third lake, Albert Nyanza (Sir Samuel Baker: a Memoir, by D. Murray, p. 97). A relief expedition, the funds for which had been raised by public subscription (February 1861), and the command of which had been given to Consul Petherick, was a failure, through the difficulties it experienced en route and the illness of its leader, and proved of no assistance to Speke.

Shortly after his arrival at Khartoum the foreign office received a message by telegram from Speke that all was well and the Nile traced to its source. This message created a great sensation when publicly communicated at the meeting of the Royal Geographical Society on 11 May 1863. Honours were now showered on the successful explorers. At Gondoroko Speke first heard that the founders' medal of the Royal Geographical Society had been awarded to him for the discovery of the Victoria Nyanza. On his arrival at Alexandria he was entertained by the viceroy of Egypt, and the king of Sardinia presented him with a medal with the inscription ‘Honor est a Nilo.’ He was publicly received on landing at Southampton, and a special meeting of the Royal Geographical Society was called in his honour on 22 June 1863. Speke's ‘Journal of the Discovery of the Nile’ was published in the same year and was widely read; it was translated into French in 1869, and the author was invited to Paris and presented to the Emperor Napoleon, by whom he was promised assistance if he should undertake another expedition.

The fact that Speke's proof of the Victoria Nyanza being the source of the Nile was not absolute, owing to the stream being left for a considerable distance and the Luta Nzigé (Albert Nyanza) not being visited, rendered his achievement open to some doubt, and his discoveries and theories were criticised both by Miani, the Venetian traveller, and by Burton and McQueen in their joint production, ‘The Nile Basin’ (1864). Great public interest was taken in the matter, and it was arranged that Speke should meet the most formidable of his critics, Captain Burton, and debate the subject with him at the meeting of the geographical section of the British Association at Bath on 18 Sept. 1864 [ed: 16th Sept.]. Unhappily on the morning of the day fixed for the discussion Speke, [ed: it was actually the afternoon of the previous day, 15th Sept.] who was stopping with his uncle-in-law, John Bird Fuller, at Neston Park, near Bath, accidentally shot himself fatally when partridge-shooting [ed: he was out shooting with his cousin George Pargiter Fuller]. He was buried on 26 Sept. in the church of Dowlish-Wake.

The importance of Speke's discoveries can hardly be overestimated. In discovering the ‘source reservoir’ of the Nile he succeeded in solving the ‘problem of all ages’ (Sir R. Murchison's Address to the Roy. Geogr. Soc. 25 May, 1863). He and Grant were the first Europeans to cross Equatorial Eastern Africa, and thereby gained for the world a knowledge of rather more than eight degrees of latitude, or about five hundred geographical miles, in a portion of Eastern Africa previously totally unknown. Though no great linguist, Speke was by nature thoroughly qualified as an explorer, possessing remarkable courage, an unflinching perseverance, and a rare aptitude for dealing with the savage rulers with whom he came into contact. While not altogether scientific in his geographical method, he was a good astronomer, and on the whole his reckonings were remarkably accurate. He possessed a curious geographical instinct, guiding him to correct conclusions on slender evidence. His knowledge of natural history and his skill as a sportsman proved of great service to him during his travels. By Baker he was described as a ‘painstaking, determined traveller who worked out his object of geographical research without the slightest jealousy of others—a splendid fellow in every way’ (Sir S. Baker: a Memoir, p. 97).

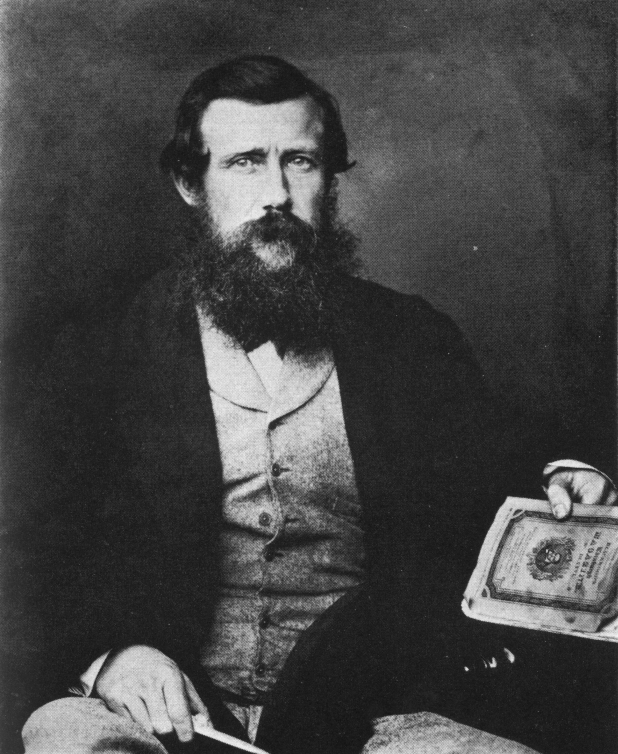

There is an engraving of Speke, by Mr. S. Hollyer, after a photograph, prefixed to the ‘Journal of the Discovery of the Source of Nile;’ and an oil painting of Speke and Grant is in the possession of Sir John Dorington; a bust, taken after death, stands in the Shirehall, Taunton; and a bust in plaster, modelled by Pieroni, is in the possession of the Royal Geographical Society. A portrait by Waterhouse, belongs to the family. A granite monument was erected by public subscription in Kensington Gardens. In 1875 an arm of the lake Victoria Nyanza was named ‘Speke Gulf’ by Mr. H. M. Stanley.

In recognition of Speke's services his family were granted an augmentation of arms with the use of supporters by royal license in 1867. Speke wrote: 1. ‘Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile,’ Edinburgh and London, 1863. 2. ‘What led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile,’ Edinburgh and London, 1864.

[Speke's publications; Times, 19 Sept. 1864; Roy. Geogr. Soc. Proceedings, 1857–63; Hitchman's Richard Burton, ii. 37, 40; Lady Burton's Life of Sir Richard Burton; Sir Samuel Baker, by T. Douglas Murray; Beke's Sources of the Nile; Speke's original maps in the possession of the Royal Geogr. Soc.; Brown's Story of Africa (1892), ii. 50–115; Lugard's Rise of our East African Empire (1893); Sir H. H. Johnston's British Central Africa, 1897, pp. 63 seq.]

Speke in 1864, holding a copy of Blackwood's Magazine.

Grant and Speke, with 'Bombay' in the background.

A cartoonist's impression, 1872

Obituary and Inquest, from the Times

17th September 1864.

HB Thomas in The Uganda Journal

(Vol 13, 1949):

THE DEATH OF SPEKE IN 1864 By H. B. Thomas, O.B.E.

YOU will find it a very good practice always to verify your references, sir!" said a centenarian sage.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th Edition, 1910-11) records: “It was arranged that Speke should meet Burton at the meeting of the geographical section of the British Association at Bath on the 16th of September and publicly debate the question of the Nile source. On the previous afternoon Speke was out partridge shooting at Box, near Bath. In getting over a low stone wall he laid his gun at half cock. Drawing the weapon towards him by the muzzle one barrel exploded and entered his chest, inflicting a wound from which Speke died in a few minutes.”

But, the Dictionary of National Biography (1921-22 Reprint) states that “it was arranged that Speke should ... debate the subject ... at Bath on 18 Sept. 1864. Unhappily on the morning of the day fixed for the discussion Speke, who was stopping with his uncle-in-law, John Bird Fuller, at Neston Park near Bath, accidentally shot himself fatally while partridge shooting. He was buried on 26 September in the church of Dowlish-Wake.”

Chambers' Encyclopaedia (1901 Edition) which is followed by Chambers Biographical Dictionary (1921-24 Reprint) says, however, “Speke was to hold a public discussion with Burton at the British Association meeting at Bath on 15th September 1864, when, on that very morning, he accidentally shot himself whilst out shooting near that city.”

Sir Harry Johnston may be relied on to embellish any story. The Nile Quest (1903), p. 172, says, “on the 21st of September 1864 Speke whilst out partridge shooting on his father’s land at Jordans near Ilminster was scrambling over a stile with his gun at full-cock. Both barrels were discharged into his body and he died within a few hours. The news was received by the British Association just as the meeting was about to commence.” Thomas and Scott, Uganda (1935), p. 9, incautiously follow Sir Harry’s lead and refer to Speke’s death on 21st September 1864 at his Somersetshire home.

With such varied records to choose from it seemed well to consult a contemporary authority; and the file of The Times demonstrates the general accuracy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica's account of events.

On the morning of Thursday, 15th September 1864, Section E (Geography and Ethnology) of the British Association at Bath assembled under the presidency of Sir Roderick Murchison who in an opening address gave a survey of general geographical progress: Speke, who was staying with his uncle. Mr. John Fuller, at Neston Park near Box, Wiltshire, some 6-7 miles from Bath, was present.

At about 2.30 p.m. on the same day Speke set out from his uncle’s house in company with his cousin. George Fuller, and a gamekeeper, Daniel Davis, for an afternoon’s shooting in Neston Park. He fired both barrels in the course of the afternoon, and about 4 p.m. Davis was marking birds for the two guns who were about 60 yards apart. Speke was seen to climb onto a stone wall about 2 feet high: for the moment he was without his gun. A few seconds later there was a report and when George Fuller rushed up Speke’s gun was found behind the wall in the field into which Speke had jumped. The right barrel was at half-cock: only the left barrel was discharged. Speke who was bleeding seriously was sensible for a few minutes and said feebly. “Don’t move me.” George Fuller went for assistance leaving Davis to attend him; but Speke survived only for about 15 minutes, and when Mr. Snow, surgeon of Box, arrived he was already dead. There was a single wound in his left side such as would be made by a cartridge if the muzzle of the gun—a Lancaster breech-loader without a safety-guard—were close to the body; the charge had passed upwards through the lungs dividing all the large blood-vessels over the heart, though missing the heart itself.

The news of Speke’s death was telegraphed to London that night in time for a brief notice only to be included in a 2nd edition of The Times of 16th September.

It had been planned that on the morning of the 16th, Section E of the British Association should hold a debate between Burton and Speke regarding the Nile sources. [I can find no confirmation of the suggestion quoted by Mr. J. N. L. Baker in hit article on ’Sir Richard Burton and the Nile Sources’ (Uganda Journal. Vol. 12. No. I. March 1948. p. 64. note 3) that the debate had been deferred from the previous day.] Speke’s death on the previous afternoon became known shortly before the session was due to begin. There was a big gathering of members, for the proposed debate had attracted much attention. Quite understandably there was some delay in commencing the proceedings: but at length Sir Roderick Murchison entered the room and after referring in moving terms to the death of Speke a unanimous vote of condolence with his relatives was adopted. Burton was able to fill the gap with a paper on ‘The Ethnology of Dahomey’.

Speke’s body had been removed to the residence of his brother, Mr. W. Speke. J.P.. at Monk’s Park. Corsham, within a mile or so of Neston Park, and here an inquest was held that afternoon (16th) by the coroner of the Liberty of Corsham (in which parish Neston Park was then situated) and a jury "composed of respectable inhabitants of the place. A unanimous verdict that "the deceased died from an accidental discharge of his own gun after living a quarter of an hour" was recorded.

An account of the British Association’s proceedings and of the inquest appear in Saturday's Times (17th September). A leading article in The Times of 19th September 1864 pays a warm tribute to Speke’s achievements and memory, but does not commit itself upon the issue of the controversy between Speke and Burton.

The tiny village of Dowlish Wake lies in the heart of Somersetshire, some two miles south-east of Ilminster and about 45 miles from Bath: and here, in the presence of his old travelling companion Grant, of Dr. Livingstone (who had returned to England two months before) and of Sir Roderick Murchison, Speke was buried. The parish church is the shrine of many generations of the Speke family, and a window and monument have been erected to the explorer’s memory. Jordans, the ancestral home and still in the hands of the Speke family, is in a neighbouring parish, Ashill, lying about 2 miles to the north of Ilminster.

Sir Roderick Murchison was responsible for launching a public appeal for a Speke memorial; and the result may be seen in the austere red-granite obelisk standing to-day in Kensington Gardens, and inscribed “IN MEMORY OF SPEKE VICTORIA NYANZA AND THE NILE 1864". There is something particularly fitting in its situation, with G. F. Watts’ ‘Physical Energy’ on the one hand, and Sir George Frampton’s ‘Peter Pan’ on the other; for Speke’s nature displayed a truly remarkable blend of indomitable determination with the spirit of perennial youth.